This story was initially printed by ProPublica and is republished right here with permission.

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of energy. Join Dispatches, a publication that spotlights wrongdoing across the nation, to obtain our tales in your inbox each week.

The spry 76-year-old girl finds her spot on the eating room desk, ready to debate an issue her household has confronted, in a single type or one other, for half a century. Again when Samaria “Cookie” Mitcham Bailey was a teen in 1964, she was among the many first Black college students to desegregate public colleges right here in Macon, Georgia. She endured the snubs and sacrifices with hope that future generations would know an equality that she had not.

All these years later, that equality stays elusive. Cookie’s hope now facilities on the kid throughout the desk.

Her 13-year-old great-granddaughter, Zo’e Johnson, doesn’t say a lot at first. Final 12 months, when she was in sixth grade, Zo’e struggled on the public center faculty, which she felt was “chaotic.” Her household canvassed their choices for one more faculty in Macon, most of them nonetheless largely segregated by race. They selected First Presbyterian Day Faculty, identified for its rigorous lecturers and Christian worldview. It additionally has a powerful tennis program, a draw for a household of tennis standouts.

However FPD isn’t simply any personal faculty. It was among the many a whole lot that opened throughout desegregation as white youngsters fled the arrival of Black college students. Black college students like Cookie.

Researchers name these personal colleges “segregation academies.” Macon was — and is — particularly saturated with them. Utilizing archival analysis and an evaluation of federal information, ProPublica recognized 5 that also function within the metropolis. They embrace the three largest personal colleges on the town. For generations, they’ve siphoned off swaths of white households who invested their extra plentiful sources in college-sized tuition, charges, and fundraisers. Immediately, most of Macon’s public colleges are almost all Black — and, due to town’s persistent wealth hole, they grapple with concentrations of poverty.

On the eating room desk on this March day, Zo’e’s household is torn over whether or not to maintain her at FPD for one more faculty 12 months — whether or not they can afford it and whether or not the associated fee is smart.

All the colleges based as segregation academies in Macon, a majority-Black metropolis, stay vastly white. FPD, with 11% Black enrollment as of the 2021-22 faculty 12 months, has the very best proportion of Black college students amongst them. Tuition at these colleges might be insurmountable to many Black households. In Macon, the estimated median earnings of Black households is about half that of white ones.

Zo’e’s household makes it work largely as a result of FPD helped them apply to get virtually half of the roughly $17,000 seventh-grade tuition paid by means of a state voucher-style program — and since Cookie has been in a position to pay the distinction. That’s about $900 a month.

However she isn’t certain she will be able to preserve paying. She just lately reduce her work hours as a medical laboratory supervisor with hopes of retiring within the subsequent few years. On the desk, her tone unusually subdued, she notes she’s had COVID-19 twice. Her reminiscence generally falters.

“I’m older,” she says. “I’m getting outdated.”

Zo’e’s mom, Ashley Alexander, is a single father or mother who works half time and can’t foot the additional invoice. She and Zo’e reside with Cookie and her husband, a retiree who as soon as labored as an legal professional.

Ashley takes a seat between Zo’e and Cookie. “I really feel such as you get the higher alternative on the Caucasian faculty. The training is healthier,” Ashley says. “It’s simply so costly. We’ve been on the lookout for some alternate options.”

However Zo’e doesn’t wish to depart FPD. She likes the Christian emphasis. And she or he appreciates the construction and the calm, each essential to a household that’s deeply protecting of her.

When Zo’e was 6, her father was shot and killed a mile away from this home. A mural of his face stretches throughout a close-by constructing, the place she generally goes to take footage and to hope. Her father had supported sending his now-adult son, who performs within the NFL, to a different personal faculty on the town. It’s one motive Zo’e thinks he could be pleased with her succeeding at FPD.

She additionally has made good pals — Black and white. She likes the difficult lecturers, the orderly courses, and, particularly, its tennis crew. Her old-fashioned doesn’t have one.

On the desk, Zo’e speaks up: “I really like FPD.”

***

As soon as sleepy, depressed even, downtown Macon is having fun with a rebirth on this metropolis that’s house to virtually 157,000 individuals. Mercer College, Cookie’s alma mater, brings collegiate vibrance. A number of grand church buildings, Catholic colleges, and a hospital add to the bustle, together with the gleaming Tubman African American Museum. In a first-floor exhibit, Cookie’s highschool commencement {photograph} hangs on an extended wall that pays tribute to college students’ work desegregating Macon’s public colleges.

Simply past the downtown streets lined with espresso outlets and eating places, and the circles of poverty that encompass them, Cookie’s brick house sits in a principally white middle-class neighborhood. She has lived on this home for 3 many years, trodding its good-looking wood flooring and adorning it with household images.

A number of weeks earlier than the eating desk dialogue, she arrives house sporting a inexperienced tracksuit from Florida A&M College, the place one in all her three daughters performed tennis. Cookie simply left a tennis event. In a good match, Zo’e beat a fellow FPD participant who had bested her a number of occasions earlier than. The opposite participant smacked her racket on the court docket, then kicked it. Cookie was thrilled. She and her husband met enjoying tennis, they usually have a number of collegiate tennis gamers of their household.

Ashley and Zo’e stroll in later with diminished enthusiasm. Zo’e misplaced her ultimate match, and she or he’s exhausted and grumpy. She heads to her bed room the place a brown teddy bear awaits together with a poster labeled “Imaginative and prescient Board.” She embellished it with phrases like “Forgive” and “School” and “God Solely.”

“She did good!” Cookie calls down the corridor.

Zo’e first dabbled in tennis when she was 6, across the time of her father’s homicide. On the court docket, she might reside within the second, pondering solely of the match at hand. It offered aid and focus, particularly when nervousness crept in.

She retains together with her a newspaper clipping about her father’s demise at 39. To some who learn information protection of his killing, he was a gang chief who hung out in jail. However she and lots of locally knew the person who wished his youngsters and others within the neighborhood to dodge the traps of life — traps she’d begun to come across on the public center faculty.

After Zo’e enrolled at FPD, Ashley started driving her every morning in the other way of the general public center faculty, which sits a mile away previous a strip mall anchored by a Household Greenback.

As an alternative, they cruised for quarter-hour towards the leafy neighborhoods to town’s north. At a stretch of white ranch fencing, they turned and drove over light hills after which veered onto the principle drive into FPD’s campus. Purple flags emblazoned with its crest grasp on avenue lamps that line the highway because it passes brick buildings, an athletic heart, expansive ball fields and a tennis advanced alongside its 248-acre campus.

Zo’e isn’t the primary in her household to attend personal faculty. Her older half-brother on her father’s aspect who performs soccer went to Stratford, a equally elite faculty on the town that additionally was based as a segregation academy. And a cousin who coaches her in tennis and is now enjoying on a scholarship at Tuskegee College went to FPD his junior and senior years. He had a principally good expertise, a giant motive Cookie took an opportunity on the college.

Even so, Zo’e felt unusual arriving on campus. At her old-fashioned, virtually 90% of her classmates have been Black. Courses have been in a single constructing, all close to each other. FPD seemed like a small school bustling with white college students. She apprehensive about what they’d consider her.

But, she felt welcomed. A lot of the children appeared good. They usually weren’t all white. About 1 in 10 was Black.

She didn’t understand it, however after George Floyd was killed in 2020, the top of faculty had issued a letter warning: “I cannot permit racism or a scarcity of respect of any variety in direction of anybody.”

As Zo’e settled in with a various new group of pals, lecturers proved her hardest adjustment. So she centered on studying examine abilities and self-discipline — and got down to show herself on the tennis court docket, which solely made Cookie prouder.

Zo’e has lived with Cookie most of her life. She calls her great-grandmother candy nicknames like Valuable. “You’re the cookie to my monster!” Zo’e wrote in Cookie’s birthday card.

A lot as she respects Cookie, the historical past of faculty segregation wasn’t on the forefront of her day by day considerations as she assimilated at FPD. However she did discover that she hadn’t seen a single Black instructor on the faculty. The one Black employees members she noticed labored as janitors or within the cafeteria.

***

Cookie’s personal journey into the world of white training started in 1964 with an announcement over the loudspeaker at her all-Black highschool. The voice sought volunteers to switch to a college for white ladies. Cookie raised her hand.

Her mom, Annie Mae Mitcham, had grown up in a rural outpost known as Cat Ridge. As a toddler within the Nineteen Thirties and Nineteen Forties, Annie Mae walked from her segregated all-Black faculty with its hand-me-down books to go clear the white children’ school rooms. She and her husband, who had a third-grade training, raised their 10 youngsters to deal with faculty achievement.

By volunteering to enroll on the white faculty, Cookie wished to see if she was as good as everybody mentioned she was. She additionally wished to know what benefits the white children have been getting — and that Black college students must have, too. She enrolled her senior 12 months.

When she arrived on the white highschool, Cookie didn’t endure the violence that many Black youngsters who desegregated colleges throughout the South did. However there was someday in English class that also, 60 years later, hurts.

A white lady turned to ask: “Do you could have a tail?”

At her outdated highschool, Cookie was an A scholar. She’d been within the marching band and the live performance band. She’d performed piano and was a stellar singer. But this white lady was evaluating her to a monkey? It reduce deeply sufficient to scar.

One thing comparable occurred to Zo’e a semester into her personal expertise at a principally white faculty. She got here house from faculty someday upset. She advised Cookie and her mom that she had discovered a pal, who’s Black, crying in a hallway saying {that a} white boy had simply known as her a “monkey.”

A month later on the eating room desk, the household revisits the monkey remark. Zo’e says she has since heard the boy who mentioned it was suspended. Her mom factors out that one scholar’s remark doesn’t outline a college.

“Let’s not make too huge a difficulty of it,” Ashley says. However for Cookie, it rips open the outdated wound from English class. She grows livid. “They’re nonetheless calling Black people monkeys!”

On the white highschool, Cookie’s academics and most college students had handled her properly sufficient. The headmistress didn’t. The steerage counselor was the worst, together with her pursed lips, pearls, and horn-rimmed glasses. When Cookie advised the counselor she wished to use at Mercer College, the lady replied with a sneer and an insult.

“Go to your personal faculty,” the lady mentioned. In different phrases, a university for Black college students. Cookie stormed from the workplace and marched to Mercer with a pal. She enrolled on her personal and finally graduated, among the many first Black college students to take action from the personal college. But, even by then, solely a smattering of Black college students had been admitted to Macon’s white public colleges. White Maconites have been battling full integration at each flip, particularly within the courts.

Extra quietly, they have been additionally busy forging one other type of resistance: They have been organizing new personal colleges for his or her white youngsters.

***

Macon sits 90 miles south of Atlanta in Georgia’s stretch of the Black Belt, a sickle-shaped swath of wealthy soil throughout the Southeast that after fueled cotton plantation riches. To protect their management after emancipation, Georgia’s white leaders segregated each aspect of life, together with the classroom. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court docket upended that when the justices dominated in Brown v. Board of Training that state-mandated public faculty segregation is unconstitutional.

White residents responded with staunch resistance.

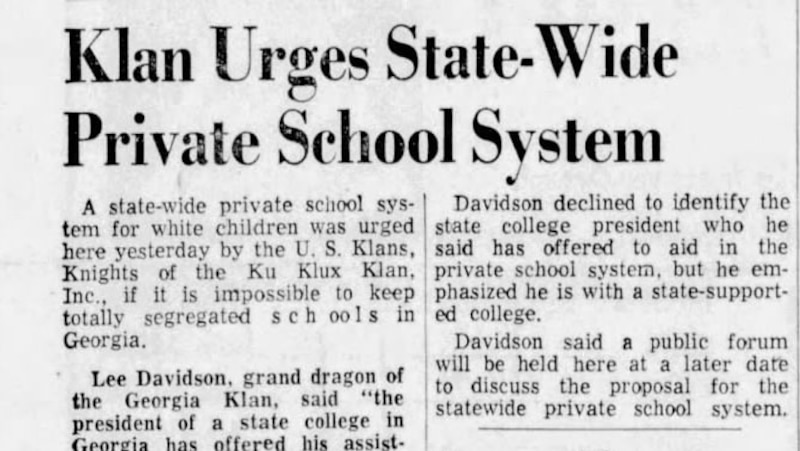

“Klan Urges State-Extensive Personal Faculty System,” a Macon Telegraph headline introduced in January 1960. Two months later, the newspaper reported {that a} native legal professional was main the cost to create an alternative choice to the county faculty system that served Macon. He deliberate a closed-door assembly with dozens of “individuals occupied with establishing a personal faculty in case the general public colleges of Bibb County are closed by the desegregation disaster.”

That fall, Stratford Academy opened. Its leaders selected the identify “due to the affiliation of the identify with Robert E. Lee and Shakespeare,” officers mentioned on the time. The varsity — nonetheless among the many metropolis’s largest and most prestigious academies — was “besieged with functions.”

As white residents fought integration, Sylvia McGee was rising up within the segregated metropolis. She had began her training at an all-Black public elementary faculty in Macon just some years after the Brown ruling. She was about to begin center faculty in 1963 when Black mother and father sued the native faculty board in what grew to become Bibb County’s key desegregation lawsuit. The case slogged on for nearly seven years.

Lastly, in February 1970, an appeals court docket compelled native colleges to desegregate — inside days. McGee was a highschool senior. Whites had fought integration for thus lengthy after the Brown resolution that she had gone by means of her total public faculty training throughout that resistance.

That fall, 5 personal colleges, together with FPD, opened in Macon, doubling the quantity on the town.

Their leaders hardly ever mentioned publicly that the colleges opened to protect all-white training. As an alternative, they nodded to “high quality” and “Christian” training.

But in fall 1970, leaders of the Southern community of the Presbyterian Church urged members to maintain their youngsters in public colleges. In a press release, they known as enforced racial segregation “opposite to the need of God” and warned towards undermining public training by establishing and supporting personal academies “whose deliberate goal or sensible impact is to keep up racial isolation.”

And even again then, some Southern newspapers known as the brand new personal colleges “segregation academies.”

“Solely the very gullible might deny that race was an element,” Andrew Manis, a neighborhood resident and historical past professor, wrote in his e-book “Macon Black and White.”

However FPD’s present spokesperson denied the college was based as a segregation academy. She advised ProPublica it “was established primarily based on the need of Macon households to supply their youngsters with a powerful training, grounded in biblical rules.” The varsity has a tuition help program and a nondiscrimination coverage, she added. She didn’t reply extra questions.

Certainly, in 1975, a number of years after it opened, FPD’s headmaster likewise advised a newspaper reporter that the college had a nondiscrimination coverage. FPD was keen to confess a Black scholar, he mentioned, “however we’ve by no means had one to use.”

To Black residents like McGee, that felt disingenuous. “The local weather and the tradition of the time mentioned you don’t apply to FPD,” she mentioned. Black mother and father would have feared for his or her youngsters’s security on the academies. Personal colleges additionally needed to undertake such insurance policies or threat shedding their tax-exempt standing.

McGee graduated in 1970 with the ultimate class earlier than full desegregation. As a result of so many white college students had fled to non-public colleges, by fall 1973, the Bibb County public faculty system was predominantly Black for the primary time.

McGee, who grew to become a social employee and finally performing superintendent till 2011, watched the district’s infrastructure crumble. Gone have been most of the white mother and father who had cash to pour into PTA fundraisers and time to fill volunteer wants.

Within the early 2000s, many years after they opened, FPD, Stratford, and many of the different academies in Macon reported that about 1% to 2% of their college students have been Black annually.

Even in recent times, Black youngsters have made up solely about 6% of most academies’ college students — in a county that’s 57% Black.

“It holds all people again,” McGee mentioned. “I believe individuals miss that time.”

***

One morning in Could, with the top of seventh grade approaching, Zo’e arrives on FPD’s campus and heads to a hallway of artwork school rooms. It stretches quiet, the partitions lined with spectacular scholar art work, courses not but beginning for the day. A number of college students sit on the corridor flooring, backs towards the wall, engrossed within the papers or cellphones in entrance of them.

For weeks, Zo’e had been dwelling in a tortuous state of uncertainty about whether or not she would return to FPD within the fall. She tried exhausting to not complain. She didn’t wish to put additional monetary strain on Cookie, who’s about to show 77, or her mother, who has sufficient on her plate.

Ashley was doing her greatest to attempt to make issues work for Zo’e. She was within the operating for a full-time job on the Bibb County Sheriff’s Workplace that might give them extra of a monetary cushion — and allow her to pay FPD’s tuition.

Now, this morning, Zo’e is about to burst with pleasure. She spots a pal within the hallway and hurries over, stifling her smile. Once they get shut sufficient, she whispers, “You understand how I advised you if my mother doesn’t get the job, I’m not going to have the ability to keep?”

Her pal appears pensive. Zo’e wrings her arms in entrance of her.

“She received the job!”

Her pal lets out a high-pitched squeal of pleasure, then glances down the corridor.

Zo’e provides, “So I’m gonna be capable of keep.”

However as the subsequent few weeks move, her hope fades. Delays creep in. Ashley’s beginning date will get pushed again.

***

The a number of generations of ladies in Cookie’s household are fast to debate the larger explanation why public colleges battle, together with Miller High quality Arts Magnet Center Faculty, the one Zo’e went to.

“There’s a motive why the academics at Miller are wired,” Cookie’s youngest daughter, Alyse Bailey, mentioned after becoming a member of her household on the eating room desk again in March. “There’s a motive why the youngsters will not be performing how they’re alleged to act. What are these causes? What are the basis causes?”

“They’re a product of the atmosphere,” Ashley responded.

“Proper, however then, why?” Alyse requested. “It’s such as you received to consistently be asking, why?”

Black youngsters lack sources, Alyse argued, due to the wealth hole stemming from slavery and Jim Crow. “The extra you return, the extra you see the place it’s rooted in systemic injustice.”

To many native households, Miller is the most suitable choice amongst public center colleges. Whereas it features as an everyday neighborhood faculty, Miller additionally attracts college students from throughout the district who attend its advantageous arts magnet element. It usually tops the district’s six center colleges on the state’s standardized exams. Virtually three-quarters of its eighth graders learn on grade degree or above in contrast with the district common of 62%. (Personal colleges don’t must launch such information.)

Faculties like Miller will quickly discover it even tougher to retain prime college students, notably these with extra sources.

Beginning subsequent 12 months, personal colleges will skim one other layer of scholars from the general public colleges. In April, as a part of a nationwide Republican push, Georgia adopted a brand new program that, much like the present one, makes use of taxpayer {dollars} to fund personal faculty tuition. At the very least 21,000 extra college students might obtain as much as $6,500 every. Final 12 months, virtually 22,000 college students tapped into the present program. The common tuition grant was about $4,600.

Supporters usually tout these packages as means for college kids to flee low-performing public colleges. However the actuality is, the schooling grants don’t usually cowl even half of personal faculty tuition payments, particularly for school prep-style colleges like FPD.

Households like Cookie’s should give you the distinction — and, if they’ll, resolve if the monetary hardship is value it.

As they wrestle with this query, Zo’e’s household places her on a ready listing for a constitution faculty that performs properly and, like most of the personal colleges, attracts giant numbers of white youngsters. However 40 college students are forward of her.

By the point summer season break arrives, Zo’e faces actuality. Her mother virtually actually gained’t begin the brand new job in time to pay looming tuition payments. Zo’e will return to the general public faculty her household felt had fallen in need of her wants. And FPD could have one fewer Black scholar.

In late June, Cookie’s birthday approaches. When her oldest daughter arrives from Florida for a go to, they lay in mattress watching tennis collectively. In dispirited tones, Cookie mentions that she can not afford Zo’e’s tuition anymore.

However her daughter presses her to suppose past FPD’s advantages to what public faculty can present, if Zo’e works exhausting and stays centered: “It’s nothing she will be able to’t get elsewhere.”

Cookie concedes, “She will get it elsewhere.” Together with Miller. She decides that the household should deal with reinforcing the educational and social self-discipline that Zo’e might want to succeed at Miller. They may also help practice her in tennis.

Within the subsequent room, Zo’e watches Disney Channel cartoons in her bed room whereas making a poster for her mother, who shares a birthday with Cookie. She glues images onto it together with a message of affection in sparkly lime inexperienced letters. Then she writes her mom a birthday be aware. “You’re not solely a life-giver however you’re a exhausting employee,” she writes. She thanks Ashley for a lot love. “You have been the one to step in when my father needed to step out. You could have been my greatest pal, a laughing buddy and a task mannequin.”

Zo’e works on the ground under her imaginative and prescient board. It features a cutout of a tiger’s eyes, intent and glued. They remind her of focus. As she accepts the probability of returning to Miller, she turns into decided to take the self-discipline she realized at FPD together with her. She additionally remembers that, right now final 12 months, she had wished to remain at Miller.

A number of weeks later, in mid-July, Ashley will get the formal job supply. She is going to turn into a sheriff’s deputy with a begin date of July 29. She is overjoyed and relieved.

It comes too late to ship Zo’e again to FPD. Public colleges are about to start the brand new 12 months. So, the household corporations up their plan for her. Zo’e will return to Miller for eighth grade to provide Ashley time to save cash for tuition. After that, when Zo’e begins highschool, they plan to ship her again to non-public faculty.

Zo’e will return to Miller for eighth grade to provide her mom time to save cash for tuition. After that, when Zo’e begins highschool, her household plans to ship her again to non-public faculty.

Mollie Simon contributed analysis.